An Introduction to Food Allergies

November 17, 2022

By: Corrie Fletcher

Categories: Allergies, Nutrition & Diet

The public often has trouble distinguishing between a food allergy and food intolerance.

You or someone you know probably carries an Epipen almost everywhere they go. Why? The CDC estimates that 10% of adults and 8% of children in the United States have experienced an allergic reaction to one or more foods. Surprisingly though, about 19% of the U.S. population self-reports having a food allergy.

Experts believe that this discrepancy in data may represent a misunderstanding of terms. The public often has trouble distinguishing between a food allergy and food intolerance.

What’s the difference?

- A food intolerance occurs when someone has trouble digesting certain compounds in foods.8 It can be very uncomfortable and can get in the way of activities of daily living, but it’s rarely serious.

- A food allergy is an immune-mediated reaction to certain proteins found in food. Severity may vary from person to person and over time, ranging from a rash to a life-threatening reaction.

The Top 9 Food Allergens

Allergens are substances that the immune system recognizes as foreign or dangerous, therefore triggering an immune-mediated reaction, or allergy. The most common food allergens in the U.S. are milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, wheat, soy and sesame.

These foods are responsible for 90% of food allergies in the United States. According to the CDC4, “the symptoms and severity of allergic reactions to food can be different between individuals and can also be different for one person over time.” Most food allergies develop during childhood. Rarely, they can also develop in adulthood, commonly shellfish allergy. Milk and egg allergies are commonly outgrown during childhood, while peanut, tree nut, fish, and shellfish allergies are generally lifelong.

Why are food allergies different in some people?

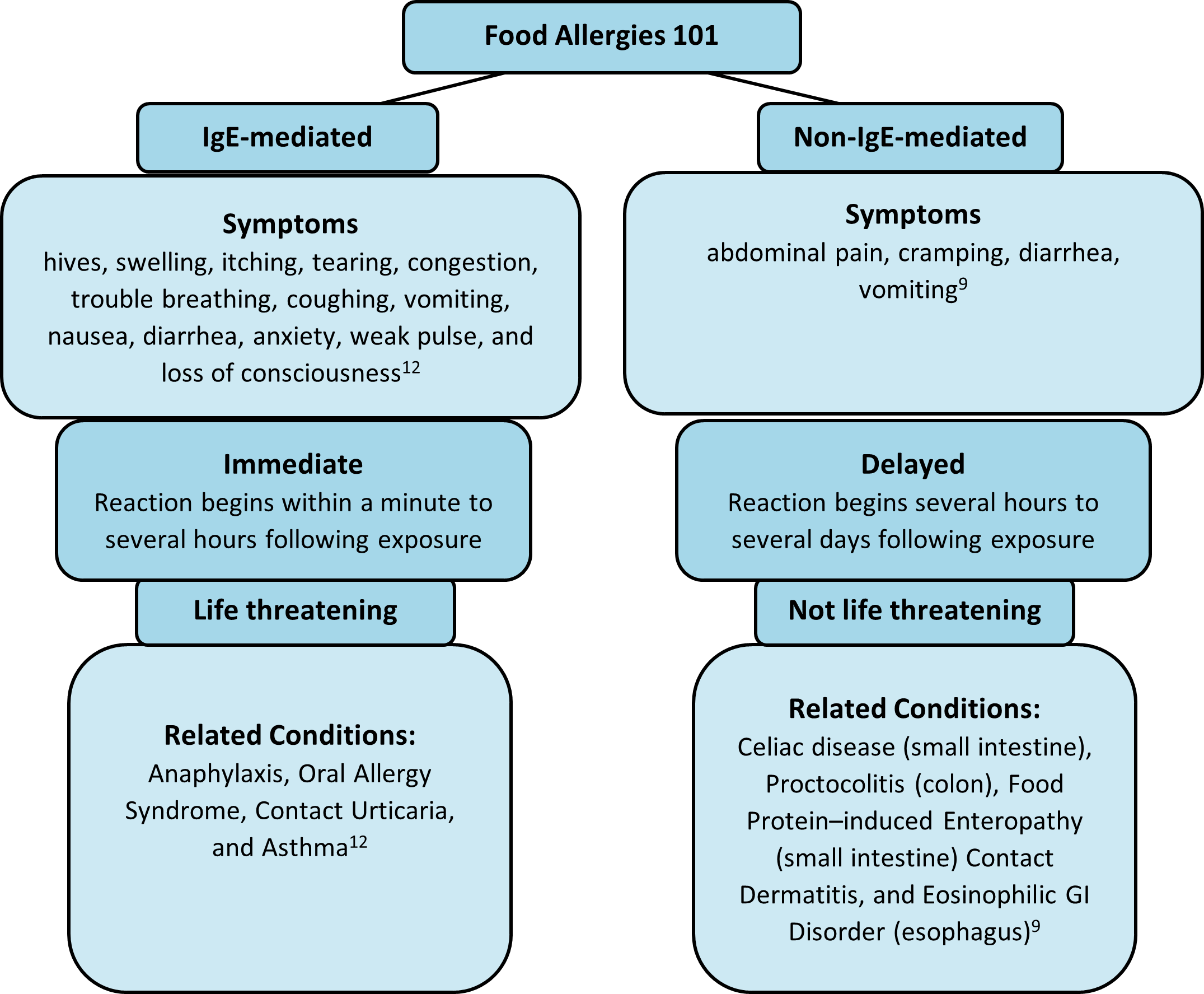

An immune response to a food allergen can be IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated. IgE stands for immunoglobulin E, which is an antibody, part of the immune system. An IgE-mediated reaction commonly involves the skin (hives or swelling), the gastrointestinal tract (vomiting or diarrhea, the cardiovascular system (low blood pressure or passing out sensation), and the respiratory tract (coughing, shortness of breath or wheezing). A non-IgE immune response is cell-mediated and is isolated to the gastrointestinal system.

Diagnosis

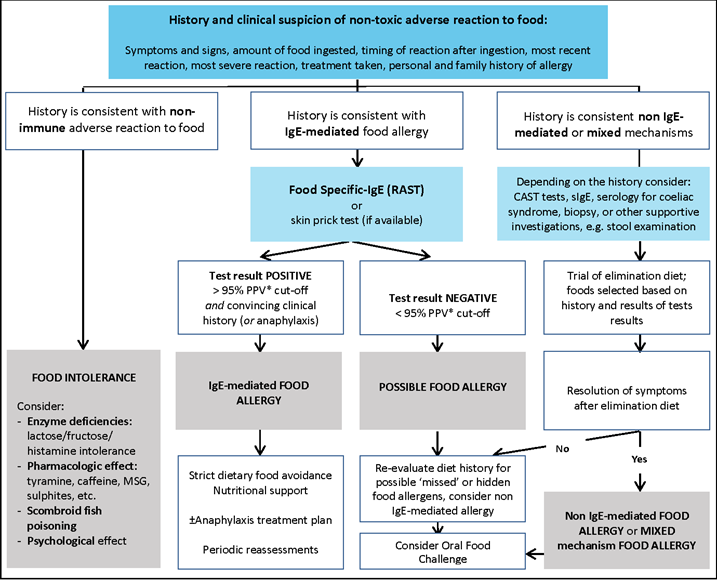

If someone has an IgE-mediated food reaction or goes to their Primary Care Provider (PCP) with symptoms consistent with such a reaction, they may be referred to an allergy specialist. The allergist will try to discern the type of food reaction by asking a series of questions about the patient's food reactions and medical history, followed by a physical exam. If an IgE-mediated allergy is suspected based on history taking, a skin prick test or food-specific IgE test is used. However, the gold standard for diagnosis of any adverse reaction to foods is an oral graded food challenge.

Diagnosing a non-IgE-mediated food allergy can be a bit more challenging. The support of a dietitian or gastroenterologist may facilitate the process. Unlike an IgE-mediated food allergy, a detailed medical history may not offer the same clues, and no quick or easy test can identify the food allergen. IgE-based skin prick of food-specific IgE tests are NOT helpful to diagnose these types of reactions. Non-IgE symptoms are also delayed, making the food allergen more difficult to pinpoint, so an oral food challenge and/or elimination diet is necessary for diagnosis. Non-IgE-mediated food allergies are associated with gastrointestinal conditions like celiac disease, proctocolitis (large intestine), and food protein-induced enteropathy (small intestine). The diagnosis of these conditions requires more invasive tests like a stool sample, x-ray, biopsy, or endoscopy.

Diagnostic algorithm for the investigation of non-toxic adverse food reactions

Management

The cornerstone of management in both IgE and non-IgE food allergies is the strict avoidance of the food allergen, followed by diet education and nutrition support. Learning how to read food labels, identify ingredients and prevent the cross-contamination of foods is vital. The elimination of important food groups will also require the introduction of nutritionally appropriate food alternatives to protect against a nutrient deficiency.

Treatment

The cornerstones for management of IgE-mediated food allergies include specific food avoidance and immediate access to epinephrine treatment. For a mild allergic reaction, an over-the-counter antihistamine can be used. This works by blocking histamine, which is the cause of these types of food reactions. For severe anaphylactic reactions, adrenaline/epinephrine auto-injectors, like an Epipen, should be used. Adrenaline is a life-saving medication that can reverse anaphylacitic reactions.

In 2020, the FDA approved PALFORZIA, the first Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) for peanuts. With OIT, a minuscule amount of the food allergen is given to a patient with a known hypersensitivity. The expectation is that the individual will become desensitized to one peanut kernel.2 This must be performed under the supervision of an allergist, as surpassing an individual's tolerance level can be life-threatening. According to Akarsu et al.,1 “The main goal of OIT is an increase in the allergen reactivity threshold to achieve a lower risk of severe allergic reactions after accidental ingestion of small amounts of allergen.” The goal is not to incorporate allergic foods back into an individual’s diet. Other allergy treatments for eggs, milk, and walnuts are in clinical trials, including OIT and epicutaneous immunotherapy (skin patch).

Unfortunately, oral immunotherapy is not appropriate for non-IgE food allergies. Non-IgE-mediated food allergy treatment primarily addresses symptoms and varies widely according to the diagnosed condition and the patient's current state of health. Medications commonly used are steroids for chronic inflammation, ondansetron for nausea, proton pump inhibitors to control acid production and promote healing, and rehydration therapy following vomiting and diarrhea. Most people's symptoms resolve within days by simply avoiding the food allergen. But sometimes, this is easier said than done.

What should I do?

- If someone has symptoms of a serious allergic reaction – such as difficulty breathing, weak pulse or loss of consciousness – seek emergency care immediately.

- If someone has mild to moderate symptoms, call your PCP or go to an urgent care clinic.

- If someone has mild symptoms that occasionally disrupt normal activities, call your PCP.

About the author

Corrie Fletcher is an intern with St. Mary’s Food and Nutrition Department. She has her Bachelor’s of Science degree in Nutrition and is currently in the Gulf Coast Dietetic Internship, which is a supervised practice program required to sit for the Registered Dietitian exam.

Physician review by Dr. Charmi Patel.

References

1. Akarsu A, Brindisi G, Fiocchi A, Zicari A, & Arasi S. Oral immunotherapy in food allergy: A critical pediatric perspective. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2022; 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.842196

2. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. The current state of oral immunotherapy. Version current 4 February 2020. Internet https://www.aaaai.org/tools-for-the-public/conditions-library/allergies/the-current-state-of-oral-immunotherapy (accessed 7 October 2022)

3. American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. Food allergies: Causes, symptoms & treatment. Version current 13 April 2022. Internet https://acaai.org/allergies/allergic-conditions/food/ (accessed 7 October 2022)

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Food allergies. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Version current 23 August 2022. Internet https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/foodallergies/index.htm (accessed 7 October 2022)

5. Cianferoni, A. Non-IgE mediated food allergy. Current Pediatric Reviews 2020, 16(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573396315666191031103714

6. Gargano D, Appanna R, Santonicola A, De Bartolomeis F, Stellato C, Cianferoni A, Casolaro V, Povino P. Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients. 2021 May 13;13(5):1638. doi: 10.3390/nu13051638. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8152468/

7. Hadley C. Food allergies on the rise? Determining the prevalence of food allergies, and how quickly it is increasing, is the first step in tackling the problem. EMBO Rep. 2006 Nov;7(11):1080-3. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400846. PMID: 17077863; PMCID: PMC1679775. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1679775/

8. Institute of Food Technologists. What is the difference between a food allergy, food intolerance, and food sensitivity? Version current 2 February 2016. Internet https://www.ift.org/career-development/learn-about-food-science/food-facts/food-allergens (accessed 7 October 2022)

9. Labrosse R, Graham F, Caubet JC. Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies in Children: An Update. Nutrients. 2020 Jul 14;12(7):2086. doi: 10.3390/nu12072086 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7400851/

10. Lloyd, M. A practical diagnostic approach to food allergies. Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology. Medicine 2015 June. 28(2). https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/EJC172584

11. National Health Service. Food allergy. Version current 6 September 2022. Internet https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/nutritional/food-allergy#treating-a-food-allergy (accessed 7 October 2022)

12. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2010, 126(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007

13. Solid Starts. Food allergens and babies. Version current 11 August 2022. Internet https://solidstarts.com/starting-solids/allergies/ (accessed 7 October 2022)